700 to 1 - The funding ratio undermining our future food system

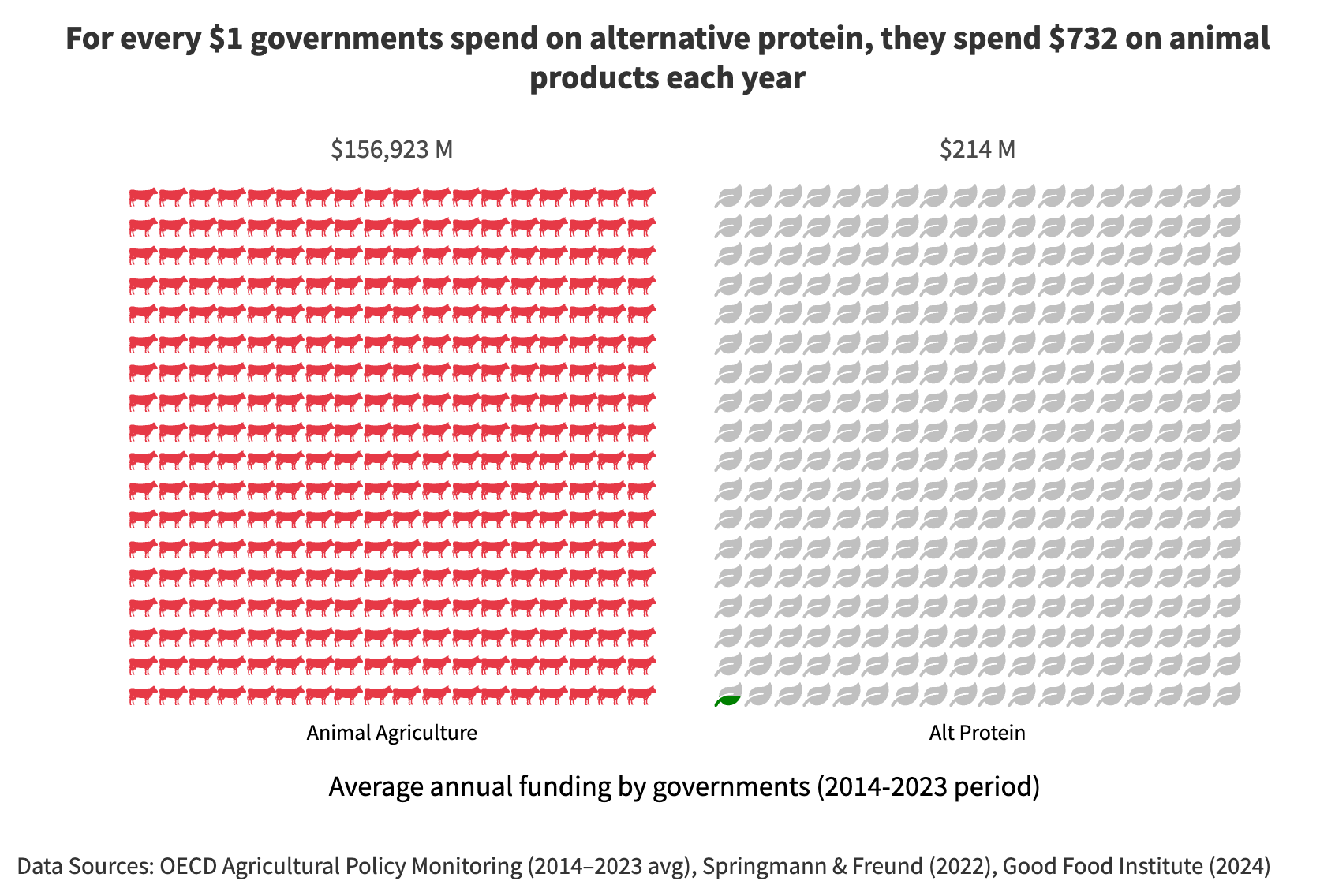

Governments provide more than 700x more funding to animal agriculture than to the alternatives that could replace them. [^ According to my analysis of data from OECD, Springmann and Freund (2022), and the Good Food Institute. I describe methods in more detail below:

Animal agriculture funding estimates: I calculated government support for animal agriculture using two main data sources. First, I obtained total government agricultural spending by country from the OECD Agricultural Policy Monitoring database (2014-2023 average). When country-level R&D data wasn’t available, I used ASTI data on public agriculture R&D spending. Second, I used allocation percentages from supplementary table 10 in Springmann et al. (2022) to estimate what portion of this spending supports meat and dairy production specifically.

Key assumption: Springmann's research focused on direct producer payments, but I apply their allocation percentages to all government agricultural spending (including R&D, extension services, etc.). This assumption is reasonable because both types of spending tend to flow to agricultural sectors based on their economic production value.

I added separate fisheries support estimates from the same OECD database to capture the full scope of animal protein funding.

Alternative protein funding estimates: I used Good Food Institute data tracking public investment in alternative proteins by country (2015-2024 average). The slightly different time period reflects data availability but doesn't materially affect the comparison (and if anything, makes it more conservative). In addition, i) I’ve assumed that research funding that has a maximum cap on spending is fully spent by researchers and ii) I’ve made a few estimates of funding sizes for undisclosed funding amounts (this is <1% of the total amount tracked)

Note: This analysis largely covers explicit government support. Some more ‘variable’ support items with unclear attribution, like market price support (think price minimums), are excluded. I excluded them because i) they’re more variable and ii) they seem more complicated to grapple with, particularly how much government is paying for the support vs. consumers (through ‘artificially’ higher prices). If we did include market price support estimates, I suspect they would likely show even larger disparities favoring animal agriculture.]

This happens despite the IPCC, Project Drawdown, EAT LANCET 2.0, and virtually every major food system assessment reaching the same conclusion: we need to diversify protein sources and eat more plants to meet climate and health goals.

When governments bet in the opposite direction, they lock in a system that effectively predetermines our food future.

A Pattern of Misalignment

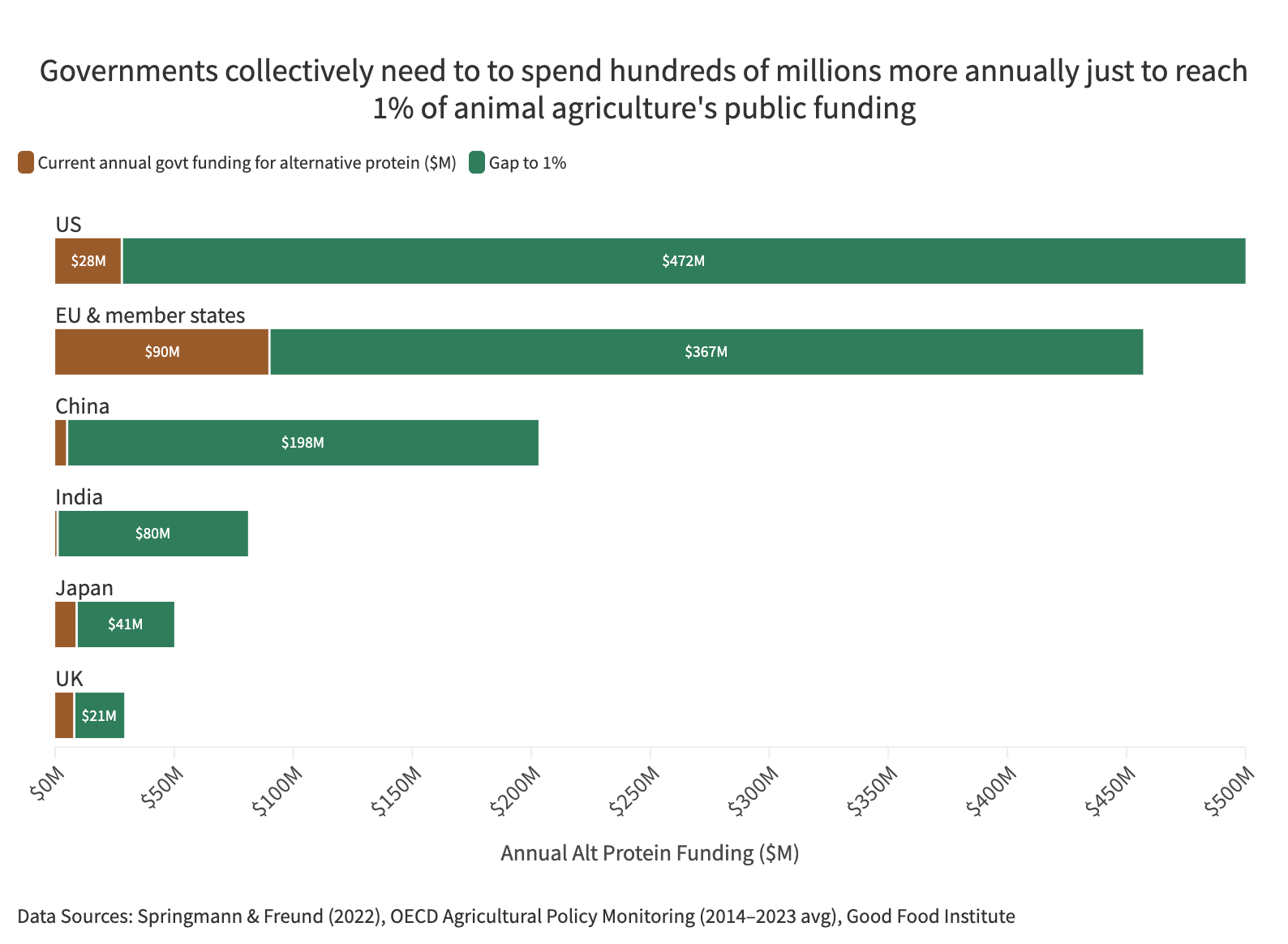

This funding disparity between animal agriculture and better alternatives shows up across every major agricultural economy. While alternative proteins account for roughly around 1% of global market share, they don't get close to 1% of the $156B that governments spend on animal products annually.

If governments merely aligned public funding with market share, they would need to allocate about $1.4 billion more each year. But market share parity shouldn’t be the benchmark. Like renewable energy, alternative proteins create public goods - like climate benefits - that markets alone won’t fund. Governments invested ~10–15% of their energy R&D budgets in renewables, for decades before those technologies reached price parity and a substantial market share. The same logic should apply to alternative proteins: early, outsized public investment can accelerate innovation and lower costs far faster than waiting for markets alone to do so.

The story looks similarly lopsided when considering a wider range of technologies and practices that could support our climate goals. For example, zooming in on research budgets and looking at data and analysis from the Breakthrough Institute, OECD, Good Food Institute, and Nelson & Fuglie, the U.S. government spends on average only 2-4% of its agricultural R&D budget on improving climate outcomes through a wider range of innovations like precision agriculture, anti-methanogenic feed additives, and cover cropping.

That shortfall matters because agriculture and land use drive roughly a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, and agriculture alone accounts for about 40% of global methane emissions, mostly from livestock. Under the Global Methane Pledge, more than 150 countries have committed to cutting methane emissions 30% below 2020 levels by 2030.

Yet, the Global Methane Status Report, launched at COP 30, finds that even if all current national plans were implemented, global methane emissions would fall by only 8%, not 30%, partly because of relative inaction on funding new agricultural practices and technologies.

Countries are not seriously funding the agricultural transition they’ve committed to, and that disconnect has become one of the clearest bottlenecks in meeting global climate goals.

Why R&D Is Where We Should Start

The scale of the funding gap means that getting to parity is likely going to be a challenge. But research and development funding may be a good place to start closing the gap.

First, we know that publicly-funded, open-access R&D works. Many of the breakthroughs driving today’s alternative protein industry trace back to decades of open, publicly funded (or at least publicly enabled) science that was never intended to create meat alternatives. Impossible Foods’ core innovation—the use of heme to recreate the flavor of meat—draws on foundational research in flavor chemistry, lipid oxidation, and protein biochemistry stretching back to the 1960s. Similarly, high-moisture extrusion, which is used to create the fibrous nature of modern meat alternatives, can also be traced back to earlier work in academia.

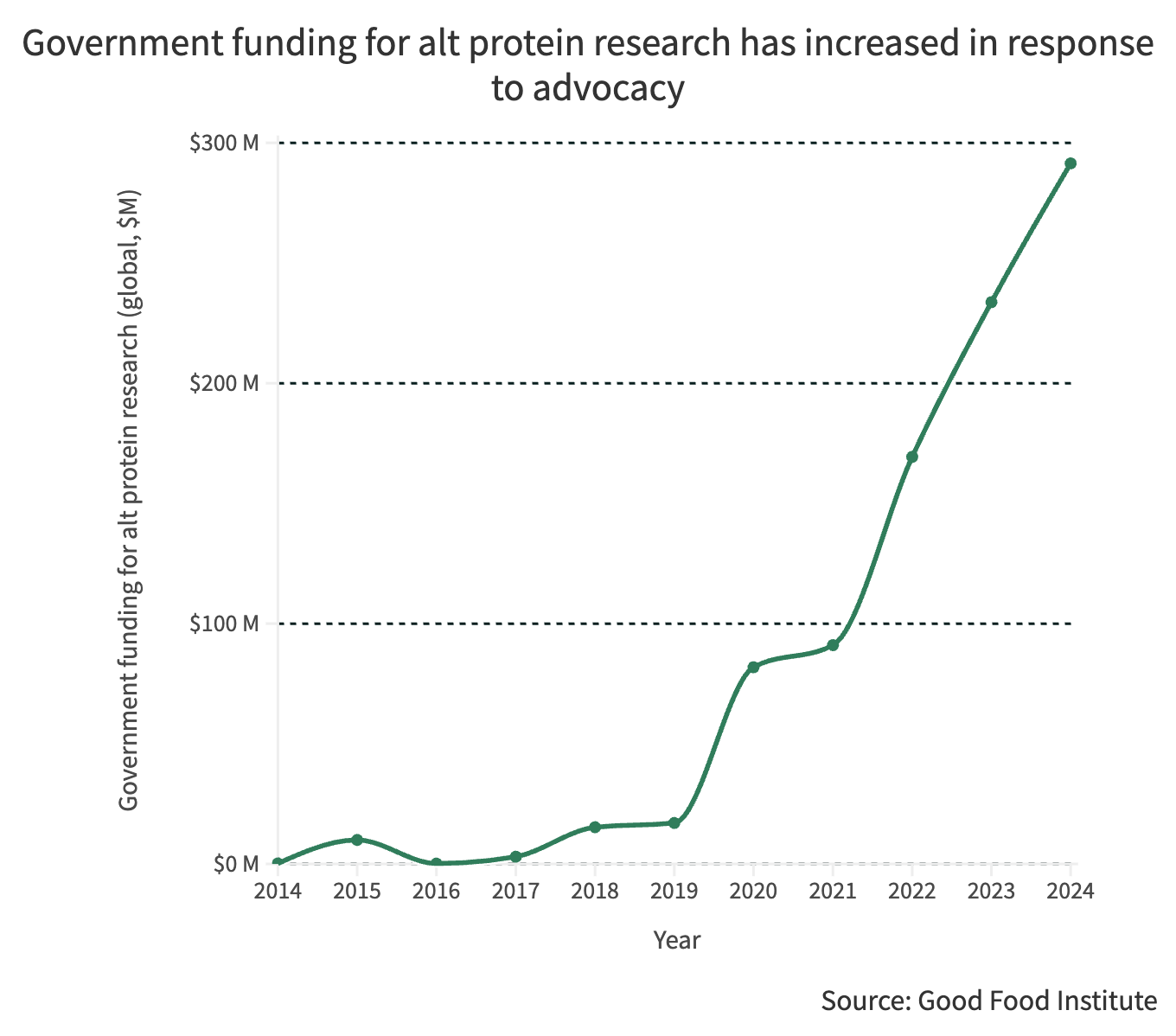

Second, we know it responds to advocacy. Ten years ago, governments were spending almost nothing on alternative protein research. That changed because advocates and researchers made the case that protein diversification is a public good. Since 2014, global public funding for alternative protein R&D has grown from essentially zero to around $290 million in 2024, raising its share of agricultural R&D from 0% to about 1.8% (based on the most recent global data for 2024) [^ The broader 700:1 ratio above uses 10-year averages (2014–2023) for all agricultural spending, which smooths volatility and missing data, while these R&D figures reflect the most recent year (2024) of a rapidly expanding category. Taken together, they show a consistent pattern: governments are still investing hundreds of times more in maintaining the old food system than in building the new one—but the R&D share is finally starting to move. For a like-for-like comparison, average annual public R&D funding for alternative proteins between 2015 and 2024 was about $91 million, equal to 0.6 % of global public agricultural R&D on average, rising to 1.8 % in the most recent year.]

Finally, it can be highly leveraged. When I analyzed the ROI of funding advocacy for public R&D, I found that for every $1 invested in advocacy, governments commit about $5 in public R&D. This kind of leverage ratio actually makes the scale of this problem more graspable for philanthropic actors. With a major philanthropic commitment to this space, we could reach 5% of global public agricultural R&D (and an additional ~$500M in research annually) by 2030.

That target would still fall short of parity between animal and alternative protein spending, but it is modest and achievable by historical standards. For example, between 2004 and 2012, governments spent $2.96 billion per year on energy R&D to address roughly 40 gigatonnes of CO₂-equivalent emissions — about $0.075 per tonne, as per IEA data. Applying the same rate of R&D spending to the 10 gigatonnes of emissions from animal products implies roughly $750 million per year in public agricultural R&D would be proportionate. While that historical energy R&D figure covers a broader mix of approaches, it’s a useful benchmark for what proportionate ambition would look like in the food sector. Given methane’s powerful but short-lived warming effects, the case for exceeding that — toward $1 billion per year — is even stronger [^ Because methane’s radiative forcing is high but its atmospheric lifetime short (~10 years), early reductions deliver rapid temperature benefits, buying time for slower sectors. I think it would be reasonable to allocate $1 billion per year in R&D across complementary approaches - alternative proteins, anti-methanogenic feedstuffs, vaccines, and low-methane genetics.]. That level of spending would not only accelerate alternative proteins but also strengthen complementary approaches to reducing livestock emissions.

The Path Forward

The $1.4 billion gap to 1% may seem huge, but we have to start somewhere — and R&D spending has already proven it can change. If we moved governments from funding 1.8% of their agricultural R&D budgets for alt protein to 5%, we’d unlock another half a billion in annual R&D funding that could give us several more innovations, perhaps even more transformational than heme & high-moisture extrusion.

But success is far from guaranteed. I think our next steps should be:

- Targeted advocacy focused on specific government R&D programs where alternative proteins could fit into existing research priorities.

- Matched funding initiatives that use philanthropic dollars to unlock bigger government commitments.

- Develop evidence-based arguments that connect alternative protein R&D to things governments already care about, where appropriate. (like economic competitiveness, food security & health)

The 700:1 funding ratio isn't inevitable. It's a policy choice renewed annually in every government budget. While the broader subsidy system seems untouchable, R&D spending isn’t. It is responsive, and it changes when people make the case for it — and that’s exactly what needs to happen now.